Composing the “Acknowledgements” is surely one of the more fun parts of a book project. You’re exhausted but relieved, maybe exhilarated that it’s done and naturally brimming with gratitude to all those who have helped you. After listing the friends who gave you those crucial tips or kept your spirits up in times of despair, you turn to the unsung heroes in the historical profession, the archivists and curators who slave away anonymously in dusty repositories to preserve, catalogue, and detail the sources historians use. I’ve worked in dozens of archives in several countries, some well organized and equipped with the latest technology (the great state archives of the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany come to mind), others little more than a room with a table and only a few handwritten notes as guides to sources (countless monasteries in Western Europe). In all of them I have met wonderful, dedicated people whom I admire and remember fondly (thanks, Sister Ann Christi, for your help at the Carmel of Vilvoorde last March, you were great, thanks!).

Except, well, how shall I put it, there are exceptions. I never quite know what to do with those in the Acknowledgements. Leave them out? Bury them under praise so faint or unlikely that everybody will see right through it? It’s delicate because who knows, you may need their assistance again some day.

I just came across Acknowledgements that take care of the problem with exemplary aplomb.

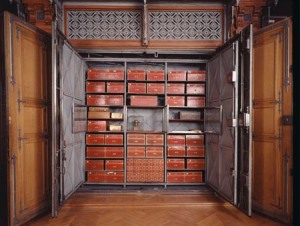

The Armoire de Fer, c. 1790, at the Archives nationales de France (photo: ANdF)

Here’s the paragraph in question cited in full from Geert Van Goethem, The Amsterdam International: The World of the International Federation of Trade Unions (IFTU), 1913-1945 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006), p. 10. Observe the firm twist of the rapier at the end:

During my more than five years of research, I visited about thirty archive centres and became acquainted with as many information retrieval systems. I adapted to thirty different sets of internal regulations, dutifully filled in registers, applied in writing to custodians for permission to consult documents, addressed governments with requests to lift embargoes, always carried passport photos so I could instantly produce some whenever required for a membership card or pass, and paid all manner of admission fees and charges. In my experience, keeping strictly to the rules usually earns one smooth and courteous assistance. But there are exceptions. In one particular instance, I had passed through all the ordeals and removed all obstacles – or so I thought. I had notified my arrival in writing from Belgium, confirmed by telephone, had had my photograph taken for a badge and even paid an admission fee for FRF 100, only to find out that I could and would not get to see the one file that had been the sole object of all my efforts. Therefore, my thanks to the Archives nationales de France need not be taken too literally.

I may add that the ANdF have a certain reputation in the field. Thanks, Geert, for showing how it’s done.

The dates of his study are still within living memory, and include the sensitive ones of 1940-45… my hunch is that there were some “Mitterands” or “Chiracs” in that file!