I made my way through Richard J. Evans’s trilogy on the history of the Third Reich, which he completed in 2008. For reasons of serendipity I read them in the reverse order, starting with The Third Reich at War covering the period 1939–1945, followed by The Third Reich in Power (1933–1939, published in 2005) and The Coming of the Third Reich (c. 1870 to 1933, published in 2003). Aimed at the general reader, the three volumes cap Evans’s lifetime of research in the era, and it shows, not so much perhaps in new revelations or extraordinary details but rather in the complete and deep command of the sources and literature displayed on virtually every one of the 2,500 pages, the lucid prose, and the ability to trace various themes over a long period without ever loosing touch with the here and now of ordinary citizens. And their victims. For, while this is not at all a blanket indictment of an entire nation and there is of course no shortage of villains at the top, Evans does make clear, it seems to me, that this is a story of people making choices, some of them tragically wrong, with catastrophic consequences for themselves and for millions of others. His central question is the same as the one asked by Friedrich Meinecke in 1946: ”How was it that an advanced and highly cultured nation such as Germany could give in to the brutal force of National Socialism so quickly and so easily?” (The Coming of the Third Reich, p. xxii). The question receives a complex answer that may serve as a much-needed warning to all of us, because, even though the specific militaristic, nationalist, and anti-Semitic traditions at the root of the process seem supremely German, they were not uniquely German, and the chances that another “advanced and highly cultured nation” makes the same mistakes seem grimly good, in my reading.

I will leave it to others with more expertise in the period than I have to review the work more thoroughly (see for instance here, here, and here –with Evans’s reply here). I have another question, much more limited in scope. Reading the trilogy in reverse yielded few original insights–I don’t recommend it. Yet, perhaps it did alert me to a few motifs that Evans did not specifically address but that caught my attention at several key turning points. One was that of the use and misuse of history. We all know examples of it from this era, but we may not know this reaction to it—or at least, I interpret the following episode as a response to the misuse of history. Speaking of the short-lived Räterepublik (Council Republic) of the so-called “coffee-house anarchists” led by Ernst Toller, which “ruled” the city of Munich for less than a week in 1919, from April 7 to 13, when it was overthrown by a Bolshevik coup, also short-lived, Evans recalls one of their measures:

Toller announced a comprehensive reform of the arts, while his government declared that Munich University was open to all applicants except those who wanted to study history, which was abolished as hostile to civilization (Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich, p. 158).

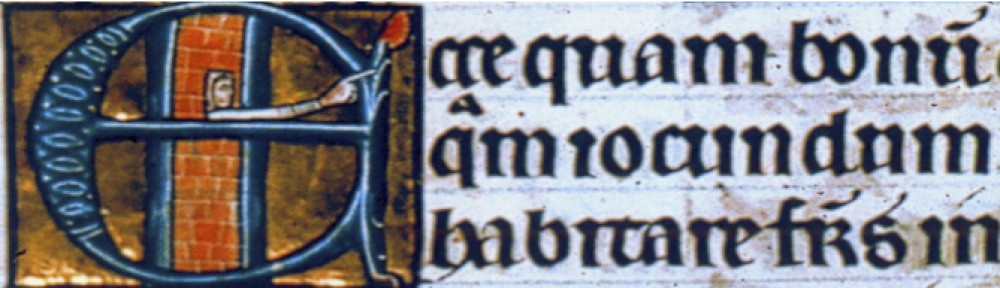

Toller’s front man for educational reform was none other than the Jewish writer and anarchist/socialist Gustav Landauer, whom I know just a little because he was, like so many romantic idealists of his age, a fervent fan of medieval culture, and a rather interesting reader of Meister Eckhart, the fourteenth-century German mystic.

Gustav Landauer, 1870-1919

Landauer’s medievalism was special, however, in the sense that he rejected its feudal and authoritarian components to embrace, in socialist-anarchist fashion, the “organic”, free-associative communities built up by guilds. Here was a fine example, Landauer argued, of the true spirit of the Volk materializing into blueprints for communal organization. Surely, at this moment in time, history had reached a high point, he thought. It all went downhill from 1500 onward, what with capitalism and science and all that modern rubbish. (As a medievalist, I heartily applaud this, though I don’t Continue reading →